Art & Art History

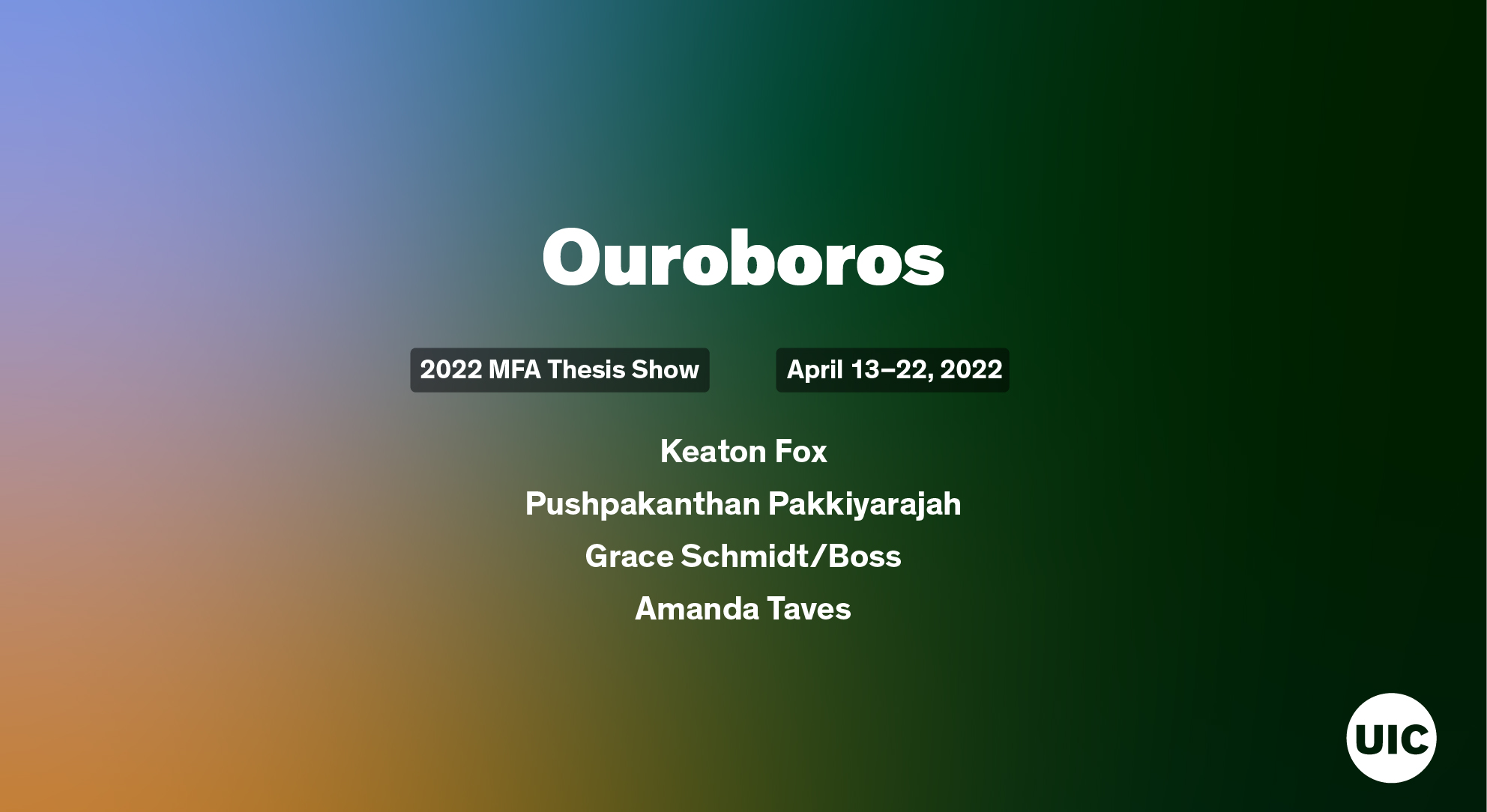

2022 MFA Thesis Show: Ouroboros

Gallery 400

400 South Peoria Street, Chicago, IL 60607

Keaton Fox, Pushpakanthan Pakkiyarajah, Grace Schmidt/Boss, and Amanda Taves

MFA Thesis Talk Friday April 22, 6-7:00pm moderated by Dianna Frid, Gallery 400 Lecture Room

Closing Reception Friday April 22, 7-9pm Gallery 400, 400 S Peoria St, Chicago IL, 60607

The second MFA class of 2022 Thesis Exhibition in Studio Arts, Ouroboros features Keaton Fox, Pushpakanthan Pakkiyarajah, Grace Schmidt/Boss, and Amanda Taves.

The image of a snake twisted into a circle to consume its own tail has been a symbol of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth since ancient times. In the exhibition, Ouroboros, artists Keaton Fox, Pushpakanthan Pakkiyarajah, Grace Boss, and Amanda Taves all explore different aspects of this cycle. Whether negotiating the devastation of death caused by war, excavating personal life in a study of FBI body farms, where donated bodies birth new ecological life, undertaking the task of recalling one’s own birth, or exploring the physical and emotional bonds of motherhood, the artists in Ouroboros update the symbol’s meaning to account for the complexity of contemporary life.

Keaton Fox grew up in the era of the personal home video camera and was raised under its observant eye. Her work engages this archive which spans the moment of her emergence into the world — an artifact of a time when video cameras were allowed in the birthing room — through her childhood’s most important moments. Having an external document of her first moments of life has propelled the artists in pursuit of an impossible goal: the task of remembering the interior experience of her birth. For as specific as her experience is, every person who has ever lived outside the womb has also shared it. Fox, thus, invites us to sit in a gynecological examination chair and engage in a process of plumbing their own memories of births. From this vantage point, we watch Fox’s birth video submerged in the pinkish-red glow of internal organs and sounds from the womb. Mining the gap between forgotten experience, subjective memory, and mediated document, Fox negotiates the event of coming into life as distinct coming into consciousness. A series of documents in a nearby “waiting room” contains maps, notations, and texts that schematize these different states of being and methods of recording. We exit the installation by parting red velvet curtains and emerge reborn.

Across sculpture, drawing and video, Pushpakanthan Pakkiyaraja explores the individual body etched with trauma as a landscape and the landscape, striated by war and furrowed by death, as a collective body. Pakkiyaraja began his intensive drawing practices as a means of channeling his haunting memories of this period. This drawing practice took on a new form and monumental scale when he translated arduously drawn loops of ink into networks of matted string that resemble hair, veins, and aspects of the human body. Mycelium and the charred landscape takes its name from the material that makes up fungal colonies, Pakkiyaraja’s string drawing brings the wounded body together with the wounded landscape, connected by the fungal agents that transform death into new life. The Palmyra fanned palm tree is a distinctive feature of Pakkiyaraja’s home in Sri Lanka and a center of its community life as it provides food, fibers, building materials, medicines. In the video named for the tree, two are the silent witness to the grief and terror occurring within the house in which they stand in front, swaying to the haunting soundtrack orchestrated by Pakkiyaraja’s collaborator, Priscilla George. In a corresponding installation, also named for the tree, it lies fallen, charred on the ground. In this final work, landscape and body merge as the tree into a bouquet, offered to both the ground and to the grieving. To reconcile the horrors of civil war that devastated his native Sri Lanka, he creates work that crosses borders.

Motherhood is a relationship that begins, first, with the flesh. Grace Boss transforms her own flesh into artworks that speak of bonds deeper than bodily tethers. After an elective surgery to restore her post-pregnancy belly, Boss also elected to keep the removed tissue and its attendant components of fat, blood, fascia, and skin, to use as and transform into materials. In photographs, Boss transforms this removed part of herself into large-scale abstractions. At many times larger than life-size, buttery yellow fat, crisscrossed with hair, capillaries, and nerves, bridge the distance between aversion and curiosity to lure us into a consideration of this biological landscape. At the center of Boss’s contribution to the exhibition is a set of works related to a small brick of soap that the artist made from the fat rendered from the flesh pictured in the photographs. In a video and ceremony-like performance, Boss uses the soap to wash the hands of her son and daughter. The same fat that housed them through gestation extends her body’s capacity to cleanse, protect, and nourish her children outside of the womb-space. Based on Biblical foot-washing rituals that span many religious practices and functions as an act of service, love, and devotion, traditions which Boss practices, her performance updates this spiritual tradition for the pandemic.

Through image and sound recordings and plant samples taken from a landscape, Amanda Taves constructs portraits that search for the ineffable qualities of loss and call attention to the ways we perceive and engage with death. Her photographic series presents images of a landscape; mowed grasses frame outcroppings of budding life centered in the image. Some bear trees, others wildflowers or native grasses. A sound installation animates these scenes with cicada chirps and the crunch of grass beneath shoes. Each growth is comprised of a different variety of plants that relates to the compositions of the soil from which the vegetation grows. In this case, the difference between plants—both what plants grow and their rate of growth— can be explained by the differences between what the bodies buried beneath them purge into the soil. Scientists at the Forensic Anthropology Research Facility in San Marcos, Texas study variances across natural burials at this “body farm.” The microbiome of the person who donated their body to science mixes with the land, climate, weather, and soil in a system of exchange between body and environment. Though trained in forensics, Taves’s approach to her artistic project searches for the remainder not accountable by this equation. Transmuted from one state to another, a loved one persists and continues to affect and transform the environment around them. Thus, each budding of new life at the gravesite is a portrait of the deceased in a new state of being that testify that it is a place of life as much death.